Nutrition

Case Study: How Overtraining Impacts Testosterone Levels

1 min read

Over-training or under-eating, or both at the same time, causes harm. But with the help of smart coaching and blood profiling it can be reversed. EDGE Ambassador and long-time blood test advocate Coach Joe Beer looks at Testosterone through the lens of a real-life case study.

The Big T

Testosterone is one of those important hormones that drives many physical functions in the male and female body. From bone density to libido, fat mass to strength, and even correct red blood cell production - testosterone is one of the many factors that have an impact. It may be associated with those wanting huge muscle mass but it's actually something many athletes should keep a sharp eye on.

Normal ranges vary in the two genders, at varying ages - with males having much higher values than females (e.g. 23 vs 1.5 nmol/L). Those following the hot topic of female athletes with high resting levels and its impact on their sports participation can see this is not just a subject of male interest [1].

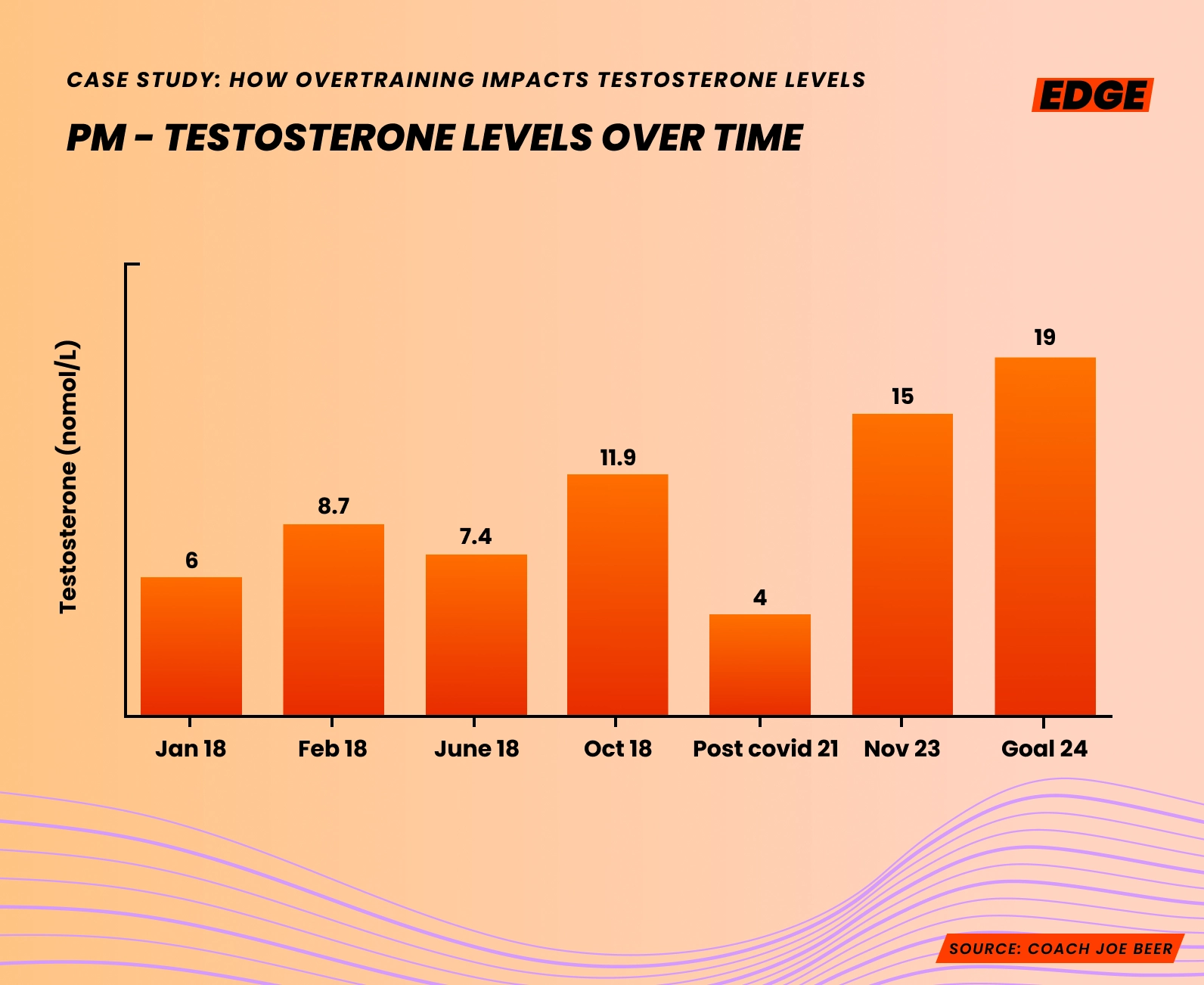

This article is going to expand upon using one male long-distance triathlon athlete (who I’ll refer to as PM for anonymity) and how training and diet together with regular testing can be used to improve blood data so that the athletes' health and well-being can be optimised.

As with all testing-for-action (as opposed to testing just to get numbers and do nothing with them), it is a simple yet effective “rinse and repeat” model really:

TEST > EVALUATE > MAKE CHANGES > PATIENCE WITH THE PROCESS

When it looks to be going wrong…

As I work with athletes every day, I’ve learned to notice the tell-tale signs that all is not right. Usually, it’s a very high training load yet poor results, signs of lowered energy or illness, or both! Soon into the process with athlete PM, it was clear bloods would be vital to see what was going on under the bonnet: It was fine to see swim speeds, bike position and even running efficiency, but these don’t tell me if all is well or has too much stress been caused by the athlete before I get to work with them. Have they dug a big hole and if so it's my job to provide the rope ladder and moral support to get them out of it.

In this case, this hole was big. And the repercussions were not just inside their sport but also outside in the real world in their personal life.

The 2018 data shows that it took a while through the early coaching interventions before new ideas in training, tweaks to diet and finally the end of a seasons events to finally see recovery, and T values in double figures.

The athlete felt better, but we were not out of the woods. The habits of training and diet are often long-term habits that reflect an athlete's psyche and to get them to change to more “fuelling” in sessions, reduce training volume and/or duration and focus on recovery is hard. Very hard.

Good coaches hold athletes back quite often to ensure they do not self-destruct, bad ones push them beyond their limits and break them.

Sorry, there is no 110%.

You have limits and good coaching is about long-term development to get 99.9% out of a person through nurture.

Note that 17nmol/L (or 500ng/dl) is a typical midpoint for males, so with values in the 6’s and 8’s it was clear this would take time. To put T values into context, I tend to see many athletes, training and eating correctly, even after 50 years of age having T values greater than 20. The moment a male gets close to 10 warning bells are already ringing in my ears that recovery, diet and training practices need a massive makeover.

You are only then aware of the extent of the task ahead

Once you can establish that values of a blood profile are on track it empowers an athlete to know they can make a difference and their values are back in their control. Mostly.

The fine line that endurance athletes tread is one where training takes out fuel and diet puts it back in, simple you may think. However many athletes are always looking to keep their body weight low to ensure that when facing gravity (e.g. a climb on a bike race course) or at any stage when running (after all, mass is the biggest factor in your run speed) they do not slow themselves down. It can also be a visual “I am not lean enough” psyche even though they appear very lean and athletic.

This food restriction habit, which is also talked about in other articles dealing with REDS (see MyFORM helped female athletes and what is RED-S in cyclists?) is a part of many athletes mindset, summed up with the horrible saying “eating is cheating”.

This calorie-counting mindset may be so ingrained that certain habits show up:

- Levels of fuelling are not reported as the athlete wants to skip around the idea they need carbohydrates in training, or afterwards

- Any estimates of fuelling are over-reported or they use phrases like “I have been good I can have some cake” or “I need to burn the pizza off later”

- When given sessions to practice fuelling at upper limits (e.g. 80g liquid carbohydrate such as Science in Sport Beta Fuel, per hour, for several hours) they repeatedly miss the fuelling target and make excuses or have no idea what little they actually did consume

The Covid impact

To put it in the case study athlete's own words (2023 quote) “During the Covid period I really lost my way in terms of concentrating on health and well-being. I took on some big personal athletic goals during this period and simply didn’t fuel appropriately in and around sessions. This resulted in a slow decline in performance and general health which left me in a pretty awful state hormonally.”

This can be seen in the graph as a plummet to just 4nmol/L which is 15-25% of the level I would expect from a healthy athlete.

We cannot turn back the clock, we can only know that the clock moves forward and we can too. The athlete sought my professional help and we continue to be in contact discussing recent VO2max data, fuel use in lab-tested sessions and general endurance sport geekiness. Most importantly, at the time of writing the athlete is targeting getting close to 20 nmol/L and has already clocked a much improved testosterone level of 15nmol/L in 2023.

They remain positive and remarked that “I fuel for the work required and live like a regular human without being overly obsessed which has slowly brought me back to full strength and health. Most importantly it has restored life wellness from a mental perspective and physical performance perspective putting out my best performance in 2023 at 40 years of age!!”

One final caution…

Training is a balance between damage and recovery. The 3-times-a-week swimmer who is in and out in under an hour “exercising” probably has little to worry about.

However, those into events which require big volumes of training like Ironman, Ultra runs, Haute Route and so on (>6h), or that involve a fair amount of weekly running - many times for several hours at a time, or those with prior body image issues that have them tending to shy away from fuelling before, during and after training - well this is where blood profiling, coached or self-coached, really is worth its weight in gold.

Athletes like PM above and others show me that we must treat our body with respect, ensuring we realise that it should not be forced to crawl forward in a state of disrepair but instead be given the TLC approach that echoes the saying (once used by sports nutrition company TWINLAB) “Feed the machine”.

Enjoy your training, your goals and the lessons along the way, most of all look after your health - your fitness and “performances” are resting on top of it.

Help your testosterone

-

Get tested

Until you know your values you are in the dark. So is your coach. Get values, get informed then get to see what you have to change and what can be left alone. Without knowing where you are on a map you have no idea which way to go next.

-

Training Balance

The key with this particular example was trying to give more emphasis on base training as it builds fitness the best way we know [2] and weeks where training was reduced to help recovery. A good rule of thumb is 3:1 ratio where 3 weeks are focussed on loading the body and 1 week on “adapting”. The longest sessions and biggest volumes of training are very personal and therefore the exact longest bike or biggest one day of all-sports only gets known as you tweak the recipe. We also looked at technologies to help keep the body recovering and the mind positive such as Lumie Light Boxes, in the athletes words: “I use a light every day, thirty mins… big change”.

-

Calorie Balance

It was also important to guide fuelling during longer sessions so that a goal was not just miles or time but actual carbohydrates consumed. For example, the goal could be 70g carbs per hour, at approximately 25g every 20 minutes throughout a 3-hour ride. In a regularly training endurance athlete we need to ensure at least 5g/kg bodyweight in carbs, so a 50kg female or 80kg male need at least 250g and 400g respectively per day. As was eluded to by the athlete quote above, this “Fuelling for the work required”[3] bonds together the person's diet with the expected demands of upcoming training. This is light years away from “eating is cheating” or “burning off calories” with more training.

-

Libido equals zero

Testosterone affects libido, when the former is low, too often the latter is also. Although this an awkward topic of discussion it is something that athletes should be aware of.

-

Get professional help?

An Edge blood test that finds testosterone, or some other metric, out of balance is not the answer, it's just a warning flag. If things are moderately off they can be soon rectified, after all, we do not know if we are getting enough B12 or de-stressed enough to keep cortisol low today or tomorrow. However, when things fall way below normal then professional help in the area may be the best next step. Seek out a dietician or sports medicine specialist(s).

Who is Joe Beer?

Coach Joe Beer has been in endurance sports since the mid-1980s. From 10k’s and half marathons came the Bath Triathlon and eventually Escape from Alcatraz Triathlon, The Ironman World Championship in Kona Hawaii to time trails, Sportives, Ultra runs and most things in-between.

Joe coaches and advises athletes of all levels from Ironman first-timers to World Marathon podium elites. He has written for magazines for over 30 years, numerous websites and has had two books published (Need to Know Triathlon – Collins, Time Crunched Triathlon – Hale). He practices what he preaches having used blood test data from the 1990’s until the present day to inform his diet and training.

-

Seiler & Kjerland (2004) Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: is there evidence for an "optimal" distribution - Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports OnlineEarly doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00418.x

-

Imply et al (2016) Fuel for the work required: a practical approach to amalgamating train-low paradigms for endurance athletes Physiol Rep, 4 (10), 2016, e12803, doi: 10.14814/phy2.12803

Read Next...

Get expert advice to help you improve your results.

Go to our knowledge centerGet 10% off your first order

Want regular tips on how to make the most of your results? Join our newsletter and we'll give you 10% off your order!